This blog post is the first in a series on a recent book by James D. Gifford, Jr. titled The Hexagon of Heresy: A Historical and Theological Study of Definitional Divine Simplicity (Wipf & Stock, 2022).

This blog post is the first in a series on a recent book by James D. Gifford, Jr. titled The Hexagon of Heresy: A Historical and Theological Study of Definitional Divine Simplicity (Wipf & Stock, 2022).

I have several reasons for interest in this book.

First, its discussion of “definitional divine simplicity” (DDS), which modern philosophers of religion more commonly call absolute divine simplicity, reinforced for me a conclusion I reached some 8 years ago. My conclusion was that DDS—the thesis that everything intrinsic to God is identical to God—leads to either (a) modal collapse or (b) providential collapse. (I borrow the latter term from Joe Schmidt.) That is, either all of reality is metaphysically necessary because everything is implicated in God’s metaphysically necessary essence, or God is absolutely indifferent to all non-divine realities and thus literally couldn’t care less about creation. Either result is theologically disastrous, resulting in top-down pantheism and/or occasionalism on the modal collapse side and extreme deism and/or atheism on the providential collapse side.

Second, Gifford’s book connected the dots for me between cosmology, providence, and Christology. I’ve long advocated for a robustly relational model of divine providence called open theism, but I hadn’t thought all that deeply about Christology until I read Gifford’s book. He showed me that an orthodox Christology (i.e., one aligned with the early ecumenical councils) naturally goes hand-in-hand with a relational theology that gives both God and creation their full due and allows both to connect with each other at a deep level. Conversely, orthodox Christology is deeply antithetical to the DDS-infused “classical” or non-relational theism that eventually (post-Augustine) became dominant in the Christian West.

Third, the Christology/cosmology connection that Gifford highlights with his “hexagon of heresy” generalizes to any context in which we want to relate a fundamental “One” (God) with a distinct “Many” (creation). Gifford helpfully explores some of these connections, but in a historical and not in a fully systematic way. That’s where my philosophical background comes in. After reading Gifford’s book I recognized that the problems with DDS that he focuses on are rooted in something deeper, a rationalistic impulse that seeks to reduce the Many to the One and ultimately to eliminate the Many in favor of the One. It’s this impulse that gives rise to DDS. After realizing this I spent several weeks thinking through the Christological and cosmological dialectic that Gifford documents, tracing out parallel “hexagons” with respect to divine providence, soteriology, religious epistemology, ecclesiology, sacraments, the Trinity, and so forth. (Gifford has helped me significantly with this in private conversation. We’ve been chatting back-and-forth for about a year now.)

My plan for this blog series is to summarize Gifford’s book and present my reflections on the broader dialectic that his book brings to light. I won’t cover historical developments (ecumenical councils, etc.) in detail. Readers can consult the book for that—Gifford’s book is dense reading, but very insightful. My approach will be thematic, beginning with the underlying dialectic (post #1), then Christology (post #2), then cosmology/providence (post #3), and finally constructively expanding the “hexagon of heresy” into other domains (post #4).

That said, let’s begin.

The Problem of One and the Many

When we look around we encounter a world with a diverse plurality: people, animals, plants, minerals, stars, ideas, sensations, etc. This plurality, however, is obviously not a brute plurality—it’s not a random chaos where anything and everything is possible. It has structure. It has limits. This allows us conceptually to organize reality and, to some extent at least, make sense of it.

Some 2600 years ago, a group of ancient philosophers known today as the Presocratics became dissatisfied with the crude polytheism of their pagan forbearers in which the “gods” and the rest of reality were thought to have spontaneously emerged from a primordial chaos. The gods imposed some semblance of order on the rest of the chaos, but were themselves fickle and unreliable, often fighting among themselves and engaging in all the sorts of stupidity to which humans themselves are prone. The Presocratics reckoned that this was no proper way to run a universe and so scrapped the pagan pantheon and sought for a more stable and fundamental ground for reality. Noting that reality had structure, they looked for ways to account for that structure. They looked for an explanatory unity (a One) amid the plurality (the Many).

Some looked for a material principle of unity. Thales thought that water might be the fundamental element. Anaximenes thought it might be air. Heraclitus thought it might be fire. Before long, however, they started thinking that the unity of reality must be something more mind-like. Thus, Empedocles proposed that in addition to the four material elements (earth, air, fire, and water) there were two motive principles, love and strife, that explained why the elements combined or opposed each other in the ways they did. Anaxagoras went further and said that the fundamental principle was nous (mind). There was a unified guiding intelligence behind the cosmos. Still other Presocratics sought for unity in something quite abstract. Anaximander thought the principle of unity was indescribable, infinite, and unlimited (Greek, to apeiron). Pythagoras thought it was number. And Parmenides thought it was an absolute and immutable principle of unity that he called the “One.”

Now, the root idea behind the Presocratic quest is a good one: When confronted with a plurality, look for an underlying principle of unity to explain that plurality. This is one of the core ideas underlying modern science. But some of the Presocratics—Parmenides most especially—pushed this idea to the extreme. He viewed the quest for unity not just as a heuristic (a guiding rule of thumb) but as a rationalistic imperative: We must transcend every plurality in order to explain its existence or even possible existence. The inevitable result of this imperative is that everything must reduce to an absolute One which, because it is beyond all plurality and all distinctions, must be “beyond being,” “beyond good and evil,” “beyond logic,” and beyond anything that could possibly give us any conceptual purchase on the One. With Parmenides, the extreme rationalistic drive for unity undermines human reason itself and bottoms out in absurdity.

Much later, Leibniz, an equally rationalistic thinker, argued that all of reality must obey an explanatory principle that he called the principle of sufficient reason (PSR). According to PSR, there must be a logically sufficient (i.e., necessitating) reason for every logically contingent state of affairs (i.e., everything that could conceivably have been otherwise). From this it follows that there can be no logically contingent states of affairs, for whatever necessarily follows from the necessary is itself necessary. Appearances to the contrary, Leibniz insisted that this is the “best of all possible worlds” and, therefore, the only possible world God could have created. The result is modal collapse: everything is necessary; nothing is contingent. An ironic consequence of rationalizing everything via PSR is again a kind of absurdity because, if all of reality is an eternally frozen block of absolute, immutable necessity, then no room is left for the activity of sense-making. In short, we can’t make sense of our own ability to make sense of things.

In general, the problem of the One and the Many is to find intrinsic unity within an otherwise chaotic Many. On the one hand, without any intrinsic unity, the Many is a meaningless chaos, a random jumble. On the other hand, if we insist on reducing the Many to an absolute unity, then everything fuses into an undifferentiated whole and we lose the possibility of any conceptual contrast by which we can meaningfully say that something is this and not that. Both of these extreme “solutions” to the problem of the One and the Many are dead ends. One “solves” the problem by eliminating all unity. There is just a brute Many and no One. The other “solves” the problem by eliminating the Many. There is only the One. Obviously, if we’re going to do full justice to our own experience, then some kind of balance must be struck. A true solution must posit a fundamental One that is also in some sense irreducibly Many. Ideally, we would also want to make sense of this fundamental unity-in-difference by showing how its inherent many-ness follows from its own unity. The Christian doctrine of the Trinity offers one possible solution, and perhaps the only solution. There are different models of the Trinity, but any good model posits a fundamental principle of unity—either the Father or the divine essence—and holds that that principle inevitably requires a Trinitarian plurality, such that the One is, necessarily, also a Many.

DDS and the Hexagon of Heresy

But if we define the One as an absolute unity—this is why Gifford speaks of “definitional” divine simplicity (DDS)—then there can be no mediating solution. If the One is absolute, then nothing in the One can reflect the many-ness of the Many. Its many-ness—that is, its status as Many—must be excluded from the One. This means that either

- The One includes the Many by negating its many-ness. This is the monist solution whereby the Many is absorbed into the One and thus does not exist as Many.

- The One utterly excludes the Many. This is the dichotomist/dualist solution whereby neither the One nor the Many have anything to do with each other. From the perspective of each, it is as if the other does not exist.

Sane people of commonsense cannot tolerate either of these extremes. They have a choice, either reject DDS or affirm DDS but mask or obscure its stark implications by pretending that those implications don’t follow and trying instead to “damage control” the One–Many tension by shifting from the fundamental category of existence/being (whether something is) to a conceptually less fundamental category like essence/nature (what something is) or energy/action/event (what something does; what’s happening). The different categorical levels at which people try to damage control the One–Many tension under DDS generate what Gifford calls the “hexagon of heresy” (hereafter, the Hexagon).

Side note #1: The categories of existence, essence, and energy are not the only levels at which one might try to mitigate the fallout from DDS. In theory one could try to do so at the level of mode/trope/state/accident (how something non-essentially is) or at the level of relation (how something relates to other things). Doing so could in principle generate an octagon or decagon of “heresy.” But these distinctions are somewhat less clear than existence, essence, and energy and in some cases overlap with those. For example, there are many different kinds of relation (logical, causal, spatial, etc.); logical ones are essential and (efficient) causal ones are energetic. Likewise some modes/states/etc. are energetic, e.g., that I am now sitting is due to my activity of sitting down. Because too many distinctions muddies the water, I’ll stick with the three that figure most prominently in Gifford’s analysis.

Of course, attempts to damage control the One–Many tension while holding on to DDS are ultimately exercises in self-delusion. The problem is that DDS functions like an equals sign (=). If everything in the One is (=) the One, then the One’s existence = the One’s essence = the One’s activity/energy. So all attempts to contain the fallout of DDS to a metaphysical level less inclusive than existence/being are unstable and ultimately doomed to failure. Humans, however, are very good at self-deception. For various reasons, many Christians (and Jews and Muslims) continue to affirm DDS while vainly fooling themselves that the fallout can be contained in a way that is religiously adequate.

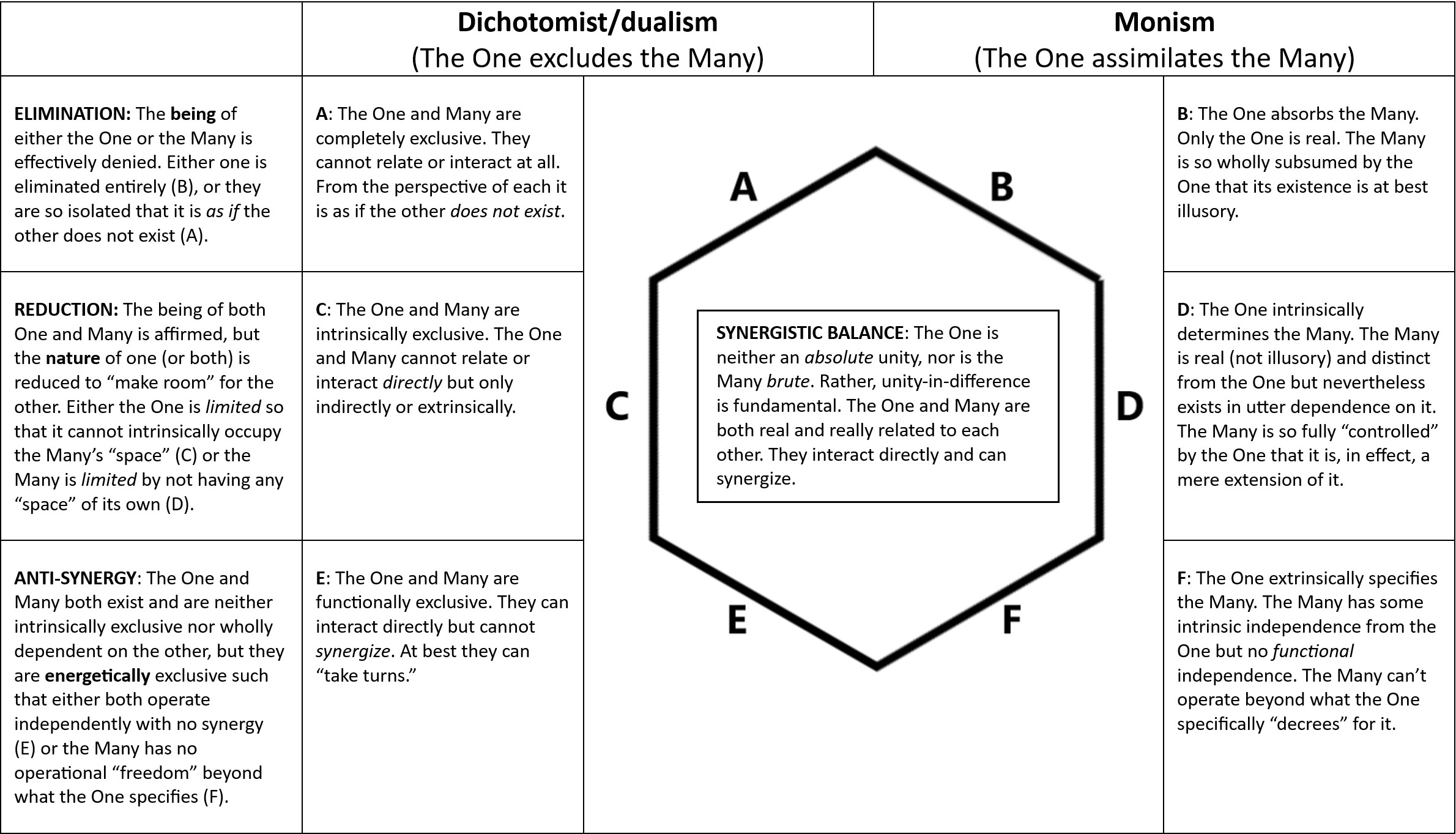

The graphic below is my reconstruction of the Hexagon as it pertains to the problem of the One and the Many. Open the image in a new tab to enlarge.

The top row expresses the basic One–Many dialectic under DDS. That is, if the One is an absolute unity, then the Many must either be absolutely excluded from the One (A) or the Many must be completely absorbed into the One (B). On the first option (A), the Many is nothing but pure chaos, having no unity whatsoever. Either there is no One at all, or the One has no connection at all with the Many. From the perspective of each it is as if the other does not exist. On the second option (B), the One doesn’t even allow the Many to exist. There is only the One and nothing else. Either way, the implications of the dialectic play out at the fundamental level of existence/being.

The second row attempts to contain the dialectic to the level of essence/nature. We suppose that both the One and the Many can exist without tension. Because an absolute One is intrinsically opposed to the Many, however, by nature they bound each other. This leaves two possibilities. One possibility is that the Many limits the One. The One and the Many exist alongside each other with no intrinsic overlap (C). They cannot occupy the same “space.” Like two stones lying side-by-side in a river bed, then can “touch” or “see” each other, but can only interact extrinsically (i.e., indirectly or from the outside). On (C) the Many has no intrinsic unity. Whatever unity it has is projected onto it. The result is pure nominalism. The other possibility (D) is that the Many doesn’t limit the One at all. The One overcomes the boundary separating it from the Many by wholly dominating the Many (without absorbing it as in (B)). On (D) the Many has intrinsic unity, but that unity is entirely projected into it from the One. The Many, in other words, has no intrinsic facility for self-organization and so is wholly passive in relation to the One.

The third row attempts to contain the dialectic to the level of energy/action. Here we suppose that both the One and the Many exist and that the Many has its own internal structure or unity that isn’t passively received from the One. Again, because an absolute One is intrinsically opposed to the Many this means at the level of energy/action that the two cannot synergize. They are functionally or energetically exclusive. This leaves two options. On the first option (E), the Many has complete functional independence or autonomy from the One and is therefore self-organizing. The One can interact directly with the Many and make unifying “suggestions” to it, but cannot “make” the Many do anything. Moreover, because the two cannot synergize, whenever one acts in a way that bears on the other, the latter has to passively “wait” for the former with respect to that activity. As in a game of checkers, the players have to “take turns.” They cannot work together, in concert, simultaneously and with reciprocal feedback (i.e., synergistically). On the second option (F), the Many has no functional independence or autonomy from the One. Instead, the Many is functionally dominated by the One, not allowing the Many to “do” anything that the One doesn’t specifically endorse.

Each of the positions outside the Hexagon (A–F) represents a different kind of “heresy.” That is, they fail to give both the One and the Many their full due in an integrated way that allows for synergy. The position inside the Hexagon that I describe as “synergistic balance” is the “non-heretical” or “orthodox” alternative. This position flat-out rejects DDS. It rejects the absolute unity/simplicity of the One that generates the either–or tension between the One and the Many and replaces it with a both–and, unity-in-difference model. The monist right-hand side (RHS) of the Hexagon supposes that the absolute One is fundamental and that the Many is therefore wholly derivative. The dichotomist/dualist left-hand side (LHS) of the Hexagon supposes that the One and Many are co-fundamental but, because the One is absolute, they are also incompatible and exclusive. The “orthodox” alternative in the middle denies that the One is absolute and affirms instead that what’s fundamental is unity-in-difference. The One and the Many are thus fundamentally unified and compatible. They can synergize and interact directly without compromising either the unity of the One or the many-ness of the Many.

The Hexagon Illustrated: Cosmology and Providence

The Hexagon presented above is very abstract. To make matters more concrete and hopefully easier to grasp, let’s apply the Hexagon to God and creation, where “the One” = God and “the Many” = creation. The resulting dialectic has enormous implications for both cosmology (i.e., how creation relates to God) and providence (i.e., how God relates to creation).

For starters, if God is absolutely simple, then nothing “in” God can possibly reflect any of the diversity within creation. Consequently, either (B) there is no diversity within creation (and no creation either distinct from God) or (A) God and creation are essentially indifferent to one another. They can’t even “see” each other. From the perspective of each, it is as if the other does not exist. Cosmologically, (B) amounts to top-down pantheism or absolute monism. Providentially, (B) amounts to occasionalism, the thesis that God is the only actor on the stage of history. There may seem to be independent creaturely actors, but there really are no such things. Cosmologically, (A) amounts to practical atheism (as far as creation is concerned, there is no God of any relevance) and/or bottom-up pantheism (there is no transcendent God; rather, the Cosmos itself is “divine”). Providentially, (A) leads to a God who is wholly indifferent to creation. As far as both God and creation are concerned, creation is on its own.

If those options seem too stark, then one might try to damage control the dialectic at the level of essence/nature. We affirm that both God and creation are real and can in some sense “see” each other, but they cannot occupy the same “space” without one or other having to give something up—that is, without its nature being constrained by the other. If God occupies the whole space as in (D), then creation can only exist as something wholly dependent on God. God must wholly determine creation. Conversely, if creation occupies its own space as in (C), then God must remain on the periphery of that space. God and creation can only relate to each other extrinsically, from the outside. Cosmologically, (C) implies that creation subsists on its own apart from God and God has to “butt out” of its space. Providentially, (C) amounts to an extreme form of deism wherein God cannot manifest immanently in creation even if He wants to. Cosmologically, (D) amounts to a kind of qualified monism or panentheism wherein creation is analogous to God’s “body” and God is creation’s all-controlling “mind.” Providentially, (D) amounts to theistic determinism.

If those options also seem too stark, then one might try to damage control the dialectic at the level of energy/action. We suppose that both God and creation are real and that God and creation can overlap to some extent, i.e., they can interact directly. Since God is absolutely simple (DDS), however, if the fundamental opposition between the One (God) and the Many (creation) is limited to the level of energy, then it follows that either (F) creation never has any “freedom” to do otherwise than God wants, or (E) creation always has “freedom” to do otherwise that God wants. Cosmologically, (F) entails that God must specifically concur or “sign off” in order for creation to “do” anything. God doesn’t necessarily determine everything that happens as in (D), but God nevertheless bounds creation tightly so that nothing can happen that God doesn’t specifically want to happen. In a picture, God corrals creation lest the wild horses run amok—can’t have the pesky creatures foiling God’s plans, after all. Providentially, (F) amounts to meticulous providence (e.g., Molinism) whereby God unilaterally decrees “whatsoever comes to pass” albeit, allegedly, without necessarily determining everything that comes to pass. Cosmologically, (E) implies that creation develops (evolves) in complete automony from God. Creation ex nihilo is, therefore, false. Providentially, (E) amounts to process theism. God makes suggestions to creation at every step, but cannot effectively do anything in creation.

Finally, the “orthodox” position in the middle of the Hexagon holds that God and creation both exist and can mutually affect each other in real time (synergy). God is free and responsive (i.e., there is a real essence/energy distinction). God actively guides creation and can act effectively within creation, but God also affords creatures a significant degree of freedom to act contrary to how God ideally wants. Cosmologically, the world is created ex nihilo and is energetically sustained by God, but is not exhaustively specified by God. Creation has a significant degree of gifted or delegated independence. Providentially, this is open theism.

Concluding Remarks

This post has largely been my own systematization of the Hexagon that Gifford identifies. His book doesn’t supply a diagram of the Hexagon, and he restricts his focus mainly to Christology and cosmology. In my next post I will draw much more heavily on Gifford’s work and discuss the Christological analog of the Hexagon. As we’ll see, the six “heresies” around the Hexagon correspond rather closely to the six major Christological heresies rejected by the first six ecumenical councils.

We’ve talked about this a good bit, Alan. This is a really good summary and, in my estimation, a conceptual improvement upon my own work. I like the being/essence/energy distinction levels. You may hit this harder in part 2 when you get to Christology, but those categories did not seem to come to the forefront in the ancient controversies. From the taxonomy you have developed, though, the various heresies almost “had” to emerge at some point, if, as I have argued, they develop at the points where Hellenism and orthodoxy rub up against each other. I’m excited to see how you take this.

Your post here really got me thinking. This one-many problem and definitional simplicity represent the best effort of the fallen mind to make sense of both natural and supernatural reality. The real problem is that it is the product of the fallen mind. I’ve coined a saying (famous to only me and Joe) that “‘distinction is opposition’ is the fundamental axiom of the fallen mind.” It is born of the effects of the fall in us that always sees the other as opposed to us, whether they truly are or not. It is the impulse whereby the man and woman in Eden “knew they were naked” and that which caused Adam to hide from the voice of the Lord God. The fallen mind cannot, due to what was lost in the fall, conceive of “the other” without some form of opposition. Whatever is “not me” somehow seeks to compete with me, wants to eliminate me, or at the very best is unconcerned with me.

The doctrine of the Trinity, in its beauty and fullness, is the beginning of the “renewing” of the fallen mind. In the Godhead, there is true diversity of persons, yet true unity of being, essence, and purpose. Unity does not negate the diversity, nor does the diversity seek to destroy the unity. Unity and diversity are in harmony forever. The Holy Trinity is the eternal counterexample to the “fallen axiom” that distinction is opposition. It shows us that this “fundamental axiom of the fallen mind” is indeed a lie. (In the early pages of “hexagon”, I show that “distinction is opposition” is equivalent to definitional simplicity, which makes the latter a lie as well.)

Most churches and most Christians remain trapped inside this lie of the fallen mind. How do I know this? The least-taught doctrine in churches in the past several centuries HAS to be the doctrine of the Trinity. Real teaching about the Trinity is dangerous for the kingdom of darkness, because, taught well, a competing and far superior axiom emerges from it – perichoresis. Perichoresis, far from holding distinction as opposition, shows us that distinction can be (and in the new heaven and earth, WILL be) harmonious with unity. Both unity and diversity ARE what God is, so both are good and I need not fear or hate that which is not me. Perichoresis becomes the axiom of the renewed mind.

The scary thing is, the entirety of Latin (Western) Christianity, thanks to its leading “lights” Augustine and Aquinas, is built upon the axiom of the fallen mind rather than the axiom of the renewed mind. Every few centuries, we have (usually misguidedly) revolted against ourselves and tried to “reform” , but we never address the underlying issue and we just wind up multiplying our expression of the same axiom of the fallen mind. The very seeds of our destruction were sewn into our religious fabric from the start. That was utterly diabolical.

Jim G.

Hi Jim. Thanks for the comment. Lots to think about there. I have just a short comment for now about “distinction is opposition.” Aquinas explicitly says that somewhere, I believe. Anyways, after thinking about it a bit, I believe you’re right that the “distinction is opposition” slogan is equivalent to DDS.

If the only way to overcome opposition is to overcome all distinction, then only an absolute One can exist stably in its own right. Everything else would necessarily be unstable because of internal opposition. So the only way anything other than the absolute One could exist would be for the One to externally impose unity on it. The immediate result is theistic determinism, if not occasionalism.

Pingback: The Hexagon of Heresy – Part 2: Christology – Open Future

Pingback: The Hexagon of Heresy – Part 3: Cosmology – Open Future

Pingback: Making Sense of the Essence–Energies Distinction – Open Future