This post is about the essence–energies distinction, that is, the distinction between God’s essence and God’s energies. The distinction is central to Eastern Orthodox theology, but is largely ignored and often denied in Western Christianity. So what gives? What is this distinction supposed to be? Why do Eastern Christians think it’s vitally important? And why are most Western Christians indifferent and/or hostile to it?

This post is about the essence–energies distinction, that is, the distinction between God’s essence and God’s energies. The distinction is central to Eastern Orthodox theology, but is largely ignored and often denied in Western Christianity. So what gives? What is this distinction supposed to be? Why do Eastern Christians think it’s vitally important? And why are most Western Christians indifferent and/or hostile to it?

These are some of the questions I’m going to tackle. Along the way I take issue with some common affirmations of both Eastern and Western Christianity.

Against the West, I argue that the essence–energies distinction is vitally important and that it should not be neglected, much less denied. Without some such distinction one cannot make sense of (a) divine freedom, (b) divine responsiveness to creation, (c) the Incarnation, and (d) salvation as theosis, i.e., true creaturely union with God without creatures literally becoming or merging with God, and (e) divine sustaining of creation.

Against the East, I’m going as to argue (a) that there are actually two essence–energies distinctions—one is a type of “real” distinction and the other is a type of “formal” distinction—and (b) that some Eastern Christians have erroneously followed Pseudo-Dionysius into extreme apophaticism about the divine essence by drawing the essence–energies distinction in the wrong place.

My main sources for reflection on the essence–energies distinction are both recent (2023) works of scholarship by well-regarded experts: David Bradshaw, Divine Energies and Divine Action: Exploring the Essence–Energies Distinction and Tikhon Pino, Essence and Energies: Being and Naming God in St. Gregory Palamas.

1. Developing the distinction

1.1. Energy

Let’s start with energy. As Bradshaw explains (p. 3), the term “energy” comes from the Greek energeia, which comes from ergon, meaning “work.” Aristotle used the term to describe “the active exercise of a capacity, such as that for sight or thought, as distinct from the mere possession of the capacity.” From there the term took on the double meanings of “activity” and “actuality” and was contrasted with the term dunamis, which took on the double meanings of “capacity” and “potentiality.” In short, energeia came to refer both to an activity (e.g., thinking) and the fulfillment or completion of that activity (e.g., knowledge or understanding). These senses merged in Aristotle’s notion of the Prime Mover, which as “pure act” or “pure energy” was described as “thought thinking itself”—an activity that is always already completed in itself.

Because it contains, indeed is, all intelligible content, Aristotle’s Prime Mover is intrinsically intelligible. This contrasts with Plato’s conception of the Good/One as “beyond being” and, therefore, beyond intelligibility (Bradshaw, p. 6). The Neoplatonic tradition of Plotinus and his successors would later harmonize Plato and Aristotle by positing that the Good/One is the absolutely simple, ineffable source of Intellect (Nous), i.e., Aristotle’s Prime Mover. Despite demoting the Prime Mover to secondary status, Plotinus retained the Aristotelian idea that the ultimate source is “pure energy.” He thus distinguished the intrinsic energy identical to the Good/One (energeia tes ousias, the energy of its substance/essence) from the outward manifestation of that energy in the production of Intellect (energeia ek tes ousias, the energy that comes forth from its substance/essence) (Bradshaw, pp. 7–8).

In the wider Hellenistic context, the dominant senses of “energy” (energeia) were that of “activity” and of “characteristic activity, operation,” but in the New Testament, the apostle Paul restricts usage of energeia to describe “the action of spiritual agents … God, Christ, angels, or demons” (Bradshaw, p. 9). This restriction became standard in early patristic literature, with the effect that the noun energeia and the verb energein took on the dominant senses of “a capacity for action or accomplishment” and “to be active in a way that imparts an energy,” respectively (Bradshaw, p. 10). In other words, when God (or another spiritual agent) acts energetically upon creatures He bestows upon them power to do stuff. Used in this way, the Aristotelian contrast between energeia as activity/actuality and dunamis as unactualized capacity/potentiality is blurred. In both Pauline and patristic usage, creaturely activity and creaturely capacity for activity are “energized” by God. See, for example, Colossians 1:29 where Paul says that he strives according to Christ’s energy (energeia) working effectively (energoumenen) in him in power (dunamis).

Side note: The dual Pauline sense of energeia as both activity and unactualized capacity for activity is analogous to the modern distinction in physics between kinetic energy and potential energy. (I do not claim, nor does Bradshaw, that modern usage of “energy” derives in any straightforward way from Pauline or patristic usage.)

By the time we get to Gregory Palamas (1296–1359), the preeminent Eastern Orthodox defender of the essence–energies distinction, the blurring of Aristotle’s energeia/dunamis distinction is complete. Palamas does not distinguish between energeia and dunamis at all. The two terms are interchangeable for him (Pino, pp. 61–62), at least when it comes to God. In part, this is because for Palamas, practically anything we might truthfully say about God is counted as a divine “energy” (Pino, p. 59). I’ll explain below (§3.2.2) why I believe he holds this expansive (and problematic) conception of divine energies. For now, I’ll just note that for Palamas the divine essence (ousia) is unknowable by us, and so whatever we might affirm of God has to fall under the catch-all category of “energy.” The divine energies include all the things that are “around God” or “around the essence” as distinguished from the divine essence itself of which we can predicate nothing (Pino, p. 65). So, it follows that anything we might think of as a divine attribute, power, or faculty, whether positive or negative, is an “energy” of God’s.

1.2. Essence

In its most basic sense, an essence (Greek, ousia) or nature (Greek, physis) defines what a thing is and cannot not be as long as it is. The essence defines the boundaries of what a thing can do and become at every stage of its existence. It is of the essence of water, for example, that its molecules contain one oxygen atom and two hydrogen atoms, that at standard Earth surface conditions it freezes at 0°C and boils at 100°C, and that it cannot turn into (say) wine without outside help.

When used of God, ousia refers to the core of God’s being, what God is and cannot not be. God, for example, cannot not exist, cannot depend on anything else for existence, and cannot be other than the source and ground of all other actual and possible beings. To say that the Father, Son, and Spirit are homoousias (of the same essence) is to say that all three Trinitarian persons share these and other essential divine qualities in one concrete instance of the divine essence.

Side note: Unlike most other essences (e.g., humanity), the divine essence is not multiply instantiable. There can be many distinct human beings, but there can be only one God. This follows from the above-stated entailments of the divine essence. If God cannot depend on anything else for existence and if the existence of everything other than God is ontologically dependent on God, then nothing other than God can be God. If two Gods somehow existed, each would have to ground the other’s existence in which case neither would be God. So, there is either exactly one God, or there is no God at all.

As Pino notes, while the terms ousia (essence) and phusis (nature) have not always been perfectly synonymous, by the time we get to Palamas, the two terms are interchangeable (p. 51). I say more about Palamas’s conception of the divine essence below (§3.2.2).

Side note: While ousia and phusis may be interchangeable for Palamas, Bradford helpfully points out that the term ousia has in fact carried several different meanings during its long history. He distinguishes between (a) ousia as “‘reality itself,’ that which is permanently and fundamental real” (p. 181); (b) ousia as “the core reality of something, that which makes the thing what it is” (p. 181); and (c) ousia as individual substances, “distinct things that are fundamentally real” (p. 182). In sense (a) ousia carries roughly the sense of “being” or “reality” or the Latin esse. Sense (b) corresponds to the modal/metaphysical sense that I describe above. In this sense it refers to the essential “whatness” of a thing (e.g., humanity). Sense (c) corresponds to what eventually became known as a hypostasis, that is, a subsistent concrete individual (e.g., Socrates).

1.3. The essence–energies distinction(s)

Essence, as I have explained, is a modal and metaphysical concept. It defines what something must be as long as it is. A thing’s essence, therefore, cannot change. For a thing’s essence to change would be for that thing to cease existing and for it to be replaced either by something else or by nothing at all.

Now, a key question concerning God is whether God is (identical to) the divine essence. If so, then it immediately follows that God cannot change at all. But if God is free to become or not to become a creator or free to become or not to become incarnate, then God cannot be identical to the divine essence. There must instead be more to God than the divine essence. The question, in other words, is whether everything God does (or can do) is specified in the divine essence, or whether God’s essence affords God leeway to do things that are not specified in the divine essence. If the latter is the case, then we have an essence–energies distinction. What God is (essence) does not wholly define what God is able to do (energy).

In this latter case, in which God’s power exceeds the divine essence, we get a real essence–energies distinction. There really is more to God than the divine essence. There can be contingent specifications of God’s being, modes of free divine activity, that are not themselves essential to God. Let’s call these God’s contingent energies.

But this is only one kind of essence–energies distinction. The Church fathers, in fact, tended to emphasize a rather different sort of essence–energies distinction by focusing on non-contingent expressions of God such as the divine glory that Christ displayed during His transfiguration (Matthew 17:2). The thought is that God is essentially energetic. As a personal, living (Jeremiah 10:10), and loving (1 John 4:8) God, one who is the light of the world (John 8:12), God cannot not be energetic. Christ, as fully divine, always participates in and expresses the divine glory (John 17:5) but the disciples as they were then could not perceive that glory until God enabled them to do so at the transfiguration. The Church’s conception of theosis is that we Christians will eventually come to participate fully—as fully as our human nature allows—in Christ’s divine life and glory. We will become “partakers of the divine nature” (2 Peter 1:4) and will “be like Him [i.e., the resurrected and glorified Christ], for we shall see Him as He is” (1 John 3:2).

These non-contingent or natural energies of God are ways in which God must act. Unlike God’s freely becoming a creator or becoming incarnate, which are contingent, God cannot not be good, wise, loving, etc. God’s natural energies are essential because God cannot not act in these ways. Because these energies are essential, they are not really distinct from the divine essence. That is, they cannot be added to or subtracted from God’s essence in the way that being a Creator is a divine self-modification added by God’s free decision to create. The natural energies may perhaps best be thought of as formally distinct from the divine essence and from each other. As defined by Duns Scotus, two things are “formally distinct when they cannot exist separately … but nonetheless can be defined or understood without reference to the other” (Bradshaw, p. 110). In short, formally distinct things are not intrinsically identical but are nevertheless non-separable.

In the case of God, the divine essence is distinct from God’s natural energies in roughly the way that a disposition/propensity is distinct from its manifestations/actualizations. Suppose we think of God’s essence as consisting of various overlapping propensities (e.g., being good, wise, loving, etc.) that are energetically manifested by the actualization of those propensities (e.g., acting good, wisely, lovingly). We might think of these essential propensities as the source from which their manifestations come in much the same way as we think of the Sun as the source of the electromagnetic radiation that it emits. The Sun’s rays are not identical to the Sun because they do not and cannot express the whole of the Sun’s being—the Sun is more than a mere collection of rays. But the Sun’s rays are not separable from the Sun either—a Sun without any rays at all would not be a sun because it is of the essence of a sun to undergo fusion and energetically express itself through its rays. Likewise, God’s natural energies are not identical to God’s essence because they do not and cannot express the whole of God’s being—however much goodness, wisdom, love, power, etc. God manifests, there is always more to God as the inexhaustible source of those perfections. But God’s natural energies are not separable from God’s essence because it is of the essence of God to be energetic in those ways. The essentially living and loving God cannot be simply a static metaphysical principle any more than a star can be merely a densely packed collection of (mostly) hydrogen atoms.

Furthermore, just as God’s natural energies express God’s essence, God’s contingent energies express God’s natural energies. Given that the natural energies cannot exhaust the divine essence but only express it, God is essentially free with respect to how those natural energies are expressed. The contingent energies are, if you will, the particular ways in which God has freely chosen to express the natural energies. It is not essential, for example, that God creates. So creating is a contingent energetic expression of God’s. But in creating God expresses the natural energies of wisdom, love, providence, power, etc.

Summing up so far, there are two essence–energy distinctions, depending on which category of divine energies is in view:

- God’s contingent energies (e.g., creating, becoming incarnate, responding to prayers, etc.) are really distinct from the divine essence. These energies express God’s natural energies in ways that are not specified by the divine essence. Each such expression adds a determination to God’s being that didn’t have to be there.

- God’s natural energies (e.g., knowing, loving, the divine glory, etc.) are only formally distinct from the divine essence. They are distinct from (not identical to) the essence in the same way that a propensity is distinct from its manifestations because as the source of those manifestations it cannot be exhausted by them. But they are also inseparable from the divine essence because they are energetic expressions that God cannot not manifest.

Alright, so far so good. Despite the fundamentally metaphysical nature of the essence–energies distinction, however, many of the Church fathers demarcated between the divine essence and God’s natural energies in epistemological ways. In his debate with Eunomius, for example, Basil of Caesarea says:

The energies are various, and the essence simple, but we say that we know our God from His energies, but do not undertake to approach near to His essence. His energies come down to us, but His essence remains beyond our reach. (Bradshaw, p. 15; emphasis added)

Basil’s distinction here is between what we can know of God (God’s energies) and of what we can’t (God’s essence). As Bradshaw puts it, for Basil “the relevant distinction is … between God as he exists within himself and [as] known only to himself, and God as he manifests himself to others. The former is the divine ousia, the latter the divine energies” (p. 16, emphasis in original). To some extent, this epistemological gloss is natural and to be expected. The only way we can know of anything apart from ourselves is by experiencing how it acts and interacts with ourselves and with other things. We gradually discover the essence of water, for example, by observing what water does under many different conditions. Likewise, we come to know of God through what God has done in creation (Psalm 19:1), written on our hearts (Romans 2:15), spoken through the prophets (Hebrews 1:1), and revealed in Christ (Romans 5:8). In short, it is only through the divine energies that we have any access to the divine essence. Moreover, it is only to be expected that we, as finite creatures, can only grasp or experience part of God’s infinite goodness, power, love, etc. We should not expect ever to fully comprehend God’s essence. Unfortunately, many Church fathers, including Palamas, went much further—indeed overboard—with this epistemological emphasis. They held not merely and plausibly that God’s essence can only be known partially by creatures through the divine energies but that God’s essence cannot be known at all by creatures and that we can only know God’s energies. I explain below (§3.2) why I think they came to this extreme position and why it’s problematic.

2. Why the essence–energies distinction is important

Having discussed what the essence–energies distinction is, I now want to discuss why it’s important. Why do we need such a distinction? There are at least five important reasons. The first two pertain to the distinction between the divine essence and God’s contingent energies, the next two to the distinction between the divine essence and God’s natural energies, and the last pertains to both, but mainly God’s contingent energies.

2.1. Divine freedom

Without a real distinction between the divine essence and God’s contingent energies, God has no freedom of self-determination. For God to be free to create or not create, free to create this sort of world or that sort of world, free to interact with creatures in this way or that way, etc., God must be able to act in ways that are not wholly dictated by the divine essence.

2.2. Divine responsiveness to creation

If there is any creaturely freedom, then for God to act in response to creaturely choices, there must be a distinction between the divine essence and God’s contingent energies. Bible passages like Jeremiah 18:7–10 and Ezekiel 33:13–15 state quite clearly that how God acts is to some extent contingent upon what creatures do. If God’s essence dictated all of God’s actions, then God would not be able to be responsive to creatures in this way.

2.3. The Incarnation

An orthodox doctrine of the incarnation requires a distinction between God’s essence and God’s natural energies. To be one divine person with two natures, one divine and one human, God the Son must take humanity into His person. I explain in this post how I think this works. Basically, the Son sets up a “human-sized” psychological space within His own person and interfaces with Christ’s human body through that space. In this way Christ’s humanity is enhypostasized by the divine Son. This implies, in turn, that Christ’s humanity is divinized by the Son. But humanity cannot participate in the divine nature as such because God is essentially God and not a creature and humans are essentially creatures and not God. So the only way humanity can be taken into the divine person and life of the Son is by way of some aspect of God that is not identical to the divine essence. Enter God’s natural energies. Christ’s humanity was suffused with the Son’s own divine life, love, wisdom, etc. If these energies were identical to the divine essence, then an incarnation would have been impossible. So God’s natural energies must be distinct from the divine essence.

2.4. Theosis

For the same reason that there can be no incarnation without an essence–energies distinction, there can no theosis without such a distinction. Theosis is direct creaturely participation in God’s own divine life. If God was identical to His essence this would be impossible because God’s essence excludes creaturehood. But if God is essence plus energies, where the divine energies are distinct from the divine essence, then creatures can participate in God’s divine life via the divine energies. Just as we can bask in the heat and light given off by the Sun but can’t bask in the Sun’s interior on pain of immediate destruction, so we can participate in God’s natural energies and be transformed by them without having to merge with the divine essence, which would destroy our created individuality.

2.5. Divine conservation of creation

Creation is a product of God’s activity, an energetic expression of divine power. And the Bible tells us in several places that God actively (and thus energetically) sustains creation. Acts 17:28 says “in him we live and move and have our being.” Hebrews 1:3 tells us that the Son “upholds all things by the word of his power (dunamis).” Colossians 1:17 says that in Christ “all things hold together.” Now, if God is identical to the divine essence, then we can’t literally have our being “in Him” for that would bring creation into the divine essence and obliterate the Creator–creation distinction. The result would be a kind of pantheism. There are, I think, four possible alternatives:

- Continuous existential sustain (aka continuous creation): At every instant creation’s whole being is supplied by God. God recreates creation moment-by-moment.

- Continuous energetic sustain: Creation can continue to exist (in some sense) without God, but it can’t function properly, even for a moment, without being “plugged in” to the divine power source. The more fully creatures are plugged in to God, the better they function.

- Intermittent sustain: Creation can exist and function properly without divine support, but only for a limited time. Creation needs an occasional divine “recharge.”

- No sustain: God sets up creation so that it can continue to exist and function properly indefinitely, without any additional divine input.

This topic deserves an extended blog post of its own, but I believe that (b) continuous energetic sustenance is the best option.

Option (a) fails because it entails occasionalism, the view that there are no created or “secondary causes.” If every creature’s whole being is supplied by God moment-by-moment, then there is no explanatory room left for creatures to do anything. To use an example, it’s like God creates a toaster ex nihilo, but because the toaster has no existential sustain, it immediately ceases to exist and so the only way God can get the toaster to seemingly “do” anything is to recreate it again and again in slightly different configurations. Like a holographic projection, it might seem that the toaster is doing things, but in reality God is doing everything by continuously projecting the toaster into existence. In essence, (a) leads to an extreme form of theistic determinism in which we get a “docetic” creation, one that at best only seems to do anything.

Option (b) is like God creates a toaster ex nihilo but in such a way that the toaster is designed to function properly only when plugged in to a continuous power source. Unplug the toaster and it will continue to exist after a fashion, but it won’t be able to do what it’s designed to do. In similar fashion we might understand Christ’s word to the disciples in John 15:4: “As the branch cannot bear fruit by itself, unless it abides in the vine, neither can you, unless you abide in me.” To abide in Christ is, in effect, to stay plugged in to the divine power source that Christ makes available to us. (b), I submit, reflects a biblical concept and does full justice to the divine conservation passages noted above.

Option (c) is like God creates a toaster ex nihilo with a rechargeable battery pack. As long as the battery is charged, the toaster performs just fine, but because it is a finite creation it can only store so much energy, it needs a recharge from time-to-time. Without an occasional recharge its performance as a toaster eventually degrades and stops. My main issue with this option is that it doesn’t reflect the sense of continuous sustain suggested by the divine conservation texts. Under (c) there isn’t any true Creator–creature synergy. Instead, there is just serial monergy—God empowers us, then we do stuff, then God empowers us, then we do stuff, etc. While one could associate (c) with the second law of thermodynamics and argue that creation is gradually “winding down,” the Bible promises that one day there will be “a new heaven and a new earth” (Revelation 21:1) that will never run down because it will be directly and eternally sustained by God (Revelation 21:23–24). So, to the extent that it is correct at all, model (c) is at best only a temporary setup, one that eventually will be, and to some extent already is, replaced by model (b).

Finally, option (d) is like God creates a toaster ex nihilo with an infinite internal power supply. God never has to supply anything more for the toaster to exist and function perfectly well if He doesn’t want to. This option smacks heavily of deism, the view that God creates the universe and then just leaves it be. I don’t see how this option can even begin to do justice to the divine conservation passages.

If I am correct that the best model is (b) then it follows that creation is energetically sustained by God. And for this to be possible, we need an essence–energies distinction in God.

3. Why the West tends to neglect and the East tends to exaggerate the essence–energies distinction

Ironically, the source of both Western neglect and Eastern exaggeration is the same core idea: absolute or “definitional” divine simplicity (DDS). (For more on DDS, see this post.) The difference is that whereas the West applied DDS to God and equated God with the divine essence, the East applied DDS to the divine essence understood as something distinct from (i.e., not identical with) God.

3.1. The source of Western neglect

Following Augustine and later Aquinas, Western theologians generally held that God is absolutely simple, meaning that God identically is whatever God has. That is, everything in God or intrinsic to God is identical to God. This entails that God = God’s essence = God’s intrinsic attributes = God’s internal acts. If we think of God’s internal acts as God’s “energies,” then it follows straightaway that God’s essence = God’s energies, in which case there is no distinction between the two. God’s essence is to be pure act (actus purus) or pure energy, with no unactualized potency. For this reason, Western theologians in the Augustinian and Thomistic traditions often explicitly reject the essence–energy distinction because they see it as incompatible with DDS. (For a detailed explanation of why the DDS conception of God is theologically disastrous, see this post.)

Some later Western theologians, including both Roman Catholics and Protestants, many of whom reject DDS, are not ideologically opposed to the essence–energies distinction, but they have nevertheless forgotten about it under those terms. Some of them effectively reintroduce the distinction using other words because, as argued above (§2), the distinction is important, but they are historically cut off from the patristic and Biblical Greek usage of “energy” (energeia) by the intervening centuries of DDS-inspired Western denial. Without a systematic essence–energies distinction, they lack a unified way of thinking about the issues in §2 and so will generally talk independently about divine freedom, responsiveness, the incarnation, theosis, etc.

3.2. The source of Eastern exaggeration

The East, by and large, never identified God with the divine essence. That is, they didn’t hold to DDS in the Western manner. God’s essence and energies are always kept at least formally distinct. As I explain in this post, the essence–energies distinction is a vital conceptual distinction without which the Church could not have developed what has come to us as orthodox Christology. Without that distinction the heretical confusions initiated by Origen’s DDS-inspired placing of the Father–Son relationship and creation on the same level cannot be overcome. (Augustine was able to reintroduce DDS in the West only because he affirmed an orthodox Christology alongside DDS—apparently without noticing the implicit tension.)

But even though the East (after several centuries of debate) finally overcame the heretical Christological implications of DDS, the vestigial influence of Neoplatonism and its identification of God with the absolute One remained. So even though the East was prohibited by its conciliar legacy from identifying God with the divine essence (as the post-Augustinian West eventually came to do), it remained open to identify God’s essence with the absolute One. The primary catalyst for this trajectory of thought in the East was, I believe, Pseudo-Dionysius (late fifth–early sixth century AD).

3.2.1. The influence of Pseudo-Dionysius

Pseudo-Dionysius (hereafter, PsD for brevity) was a syncretistic Christian Neoplatonist. He sought to blend Christianity with Neoplatonism in the tradition of Proclus. Almost as soon as PsD’s writings first appeared in the late fifth century, he was received as a prominent early Church father, albeit one whose writings were only recently discovered. This is because he successfully passed himself off as Dionysius the Areopagite, a first-century disciple of Paul’s referred to by Luke in Acts 17:34. He even addressed some of his writings to Timothy, Titus, and the apostle John as though writing to contemporaries and equals (though he does display some deference to John). PsD’s writings were not recognized as the “forgeries” they are until the 15th century. By then, their influence on both Eastern and Western Christianity had become enormous. And there are still scholars—a small minority—who insist to this day that PsD is really a first-century authority. So the influence of his writings continues.

Upon their appearance PsD’s writings were quickly received as authoritative by Severus of Antioch (c. 459 or c. 465–538), who appealed to PsD to buttress the Miaphysite cause over against the Diophysites. From the other side of that controversy, John of Scythopolous (fl. 6th century) also defended the first-century authenticity of PsD’s writings. Later, in the seventh century, Maximus the Confessor (c. 580–662), an enormously influential Church father, wrote of PsD in glowing terms in his work On the Ecclesiastical Mystagogy: “the all-holy and truly God-revealing Dionysius the Areopagite … mysteries … were revealed by the inspiration through the Holy Spirit to that one alone” (p. 48). With such an endorsement by Maximus, it is no wonder that PsD exerted a tremendous influence on Eastern theology. Indeed, the preeminent systematizer of Eastern theology, John of Damascus (c. 675–749) cites PsD at least 41 times in his major work (p. 33, fn. 63). By the time we get to Gregory Palamas (1296–1359) we still see PsD held in very high esteem. Palamas speaks of PsD as “the great Dionysios himself” (Pino, p. 67), “the divinely inspired Dionysios” (Pino, p. 68), or simply as “the great one” (Pino, p. 71). And in the course of his dispute with Gregoras, Palamas compiled a list of patristic proof-texts “drawn exclusively from the Dionysian corpus” (Pino, p. 97).

Side note: In his writings, Thomas Aquinas quotes PsD about 1,700 times! (PsDtCW, p. 21) He apparently found PsD’s writings quite congenial to his DDS model of God.

In any case, let’s consider some of what PsD has to say about God. By far his favorite description of God is as “beyond”:

“beyond being” (p. 49, passim)

“more than ineffable and more than unknowable” (p. 61)

“beyond every assertion and denial” (p. 61)

“he transcends mind and being … is completely unknown and nonexistent” (p. 263)

“surpasses the source of divinity and of goodness” (p. 263)

Many of PsD’s descriptions of God are, taken at face value, self-refuting. There is deep irony in his describing God as “more than ineffable” (thereby “effing” the ineffable, we might say), in his implicitly claiming to know that God is “more than unknowable,” and in his asserting that God is “beyond every assertion.” But the most outrageously apophatic declaration by PsD has to be this one:

“It [i.e., God] is not soul, or mind, or endowed with the faculty of imagination, conjecture, reason, or understanding; nor is It any act of reason or understanding; nor can It be described by the reason or perceived by the understanding, since It is not number, or order, or greatness, or littleness, or equality, or inequality, and since It is not immovable nor in motion, or at rest, and has no power, and is not power or light, and does not live, and is not life; nor is It personal essence, or eternity, or time; nor can It be grasped by the understanding since It is not knowledge or truth; nor is It kingship or wisdom; nor is It one, nor is It unity, nor is It Godhead or Goodness; nor is It a Spirit, as we understand the term, since It is not Sonship or Fatherhood; nor is It any other thing such as we or any other being can have knowledge of; nor does It belong to the category of non-existence or to that of existence; nor do existent beings know It as it actually is, nor does It know them as they actually are; nor can the reason attain to It to name It or to know It; nor is it darkness, nor is It light, or error, or truth; nor can any affirmation or negation apply to it; for while applying affirmations or negations to those orders of being that come next to It, we apply not unto It either affirmation or negation, inasmuch as It transcends all affirmation by being the perfect and unique Cause of all things, and transcends all negation by the pre-eminence of Its simple and absolute nature—free from every limitation and beyond them all.”

The upshot of all this is that God, for PsD, is an metaphysical surd, a we-know-not-what beyond or behind every possible conception we might have of “It.”

Now, why does PsD say this kind of stuff about God? I think the answer is clear. He affirms DDS. That is, like a good Neoplatonist and like post-Augustinian Western theologians, he affirms that God is absolutely simple. Notice that he doesn’t, like Palamas and later Eastern luminaries, restrict his apophaticism to the divine essence. No, PsD routinely speaks of God as “beyond,” etc. And the reason he, like the Neoplatonists, held that God/the One is beyond all affirmation and negation, assertion and denial is because every assertion makes a conceptual distinction between a subject and a predicate (“S is P” or “S is not P”). If the One is absolutely simple then it is beyond all distinctions and so cannot be faithfully represented in a manner that relies on conceptual distinctions.

3.2.2. The Eastern appropriation of PsD

PsD’s writings entered the scene during the post-Chalcedonian monophysite controversy. He himself was probably a monoenergist, if not a monophysite (PsDtCW, pp. 19–21). The anti-Chalcedonians quickly endorsed PsD to buttress their case. But PsD was clever and just ambiguous enough to leave room for a pro-Chalcedonian reading. And so the Chalcedonians, not wanting to ignore a putative first-century authority and leave him as a key resource for their opponents, appropriated PsD for themselves. Maximus the Confessor was instrumental in purging “Dionysian spirituality of the interpretations that would have connected it to one or another heresy” (PsDtCW, p. 23).

As noted, though, the East was already committed to an essence–energies distinction. And so they couldn’t accept PsD’s DDS without modification. The obvious move was to shift the focus from God as the absolute One, which would have collapsed the essence–energies distinction, to God’s essence as the absolute One. This preserves the essence–energies distinction as long as we don’t identify God with the divine essence à la DDS. But just as DDS leads to extreme apophaticism about God—one can’t truly say or think anything about God because the very acts of assertion and conception distinguish subject and predicate and thereby misrepresent the absolutely simple referent—the same thing happens with an absolutely simple divine essence—one can’t truly say or think anything about it. The result is extreme apophaticism about the divine essence.

One result of this is that the essence–energies distinction shifts from being primarily metaphysical with epistemological implications to being primarily epistemological, with no clear metaphysical implications since the divine essence is so “beyond” that we can’t properly assert anything metaphysical about it. Thus, Palamas echoes PsD in saying that the divine essence is beyond all assertion and denial (Pino, p. 56) and completely ineffable:

God, whatever he is at the level of essence [Greek text omitted], since he transcends and is removed from everything, is utterly beyond every intellect, every reason, and every manner of union and participation. He is without relation, incomprehensible, imparticipable, uncontemplatable, unknowable, unnameable, and completely ineffable. (Pino, p. 53, quoting directly from Palamas)

But since even saying that is asserting something about that which allegedly nothing can be asserted—a clear self-contradiction—Palamas often speaks of going “beyond” the divine essence to God’s “superessentiality” (a term he uses of God 79 times). And even that God must transcend—to what, super-duper-essentiality?—because talking about God’s superessentiality is to also to say something positive of God, which we allegedly cannot do truly (Pino, p. 76, n. 33).

In speaking of God’s essence in this extremely apophatic manner, Palamas is applying the same logic that PsD does to an absolutely simple God: If something is absolutely simple, whether that be God or the divine essence, then anything one might say about it necessarily misrepresents it because that assertion must conceptually distinguish the “it” (S) from what is said about it (P).

The upshot of this is that everything we can truly say about God has to be deflected away from the divine essence and lumped in with the divine “energies.” As Pino puts it,

According to Palamas, then, “energy is a more or less common name of the things contemplated naturally around God,” an expansive category of divine attributes, both positive and negative. (Pino, p. 65)

3.2.3. Why extreme apophaticism about God’s essence is a really bad idea

We’ve now seen how, through the influence of PsD, the Eastern Church was eventually led to a position of extreme apophaticism regarding the divine essence and to a recasting of the essence–energies distinction in primarily epistemological rather than metaphysical terms. I now give several reasons why this was a very bad development.

First, extreme apophaticism is self-refuting. If you can’t say anything about the divine essence, then logically you cannot even say that you cannot say anything about the divine essence. The only way to be consistent is to not talk about the divine essence at all. But then what about all the Trinitarian and Christological debates that were solved (in part at least) by distinguishing between the divine essence, the divine persons, and the divine energies? If we can’t talk positively about the divine essence, then we thereby undermine the conciliar legacy.

Second, extreme apophaticism makes it impossible to define the essence–energies distinction. Ironically, in the course of defending the essence–energies distinction, which is vitally important (see §2 above), Palamas inadvertently vacates the distinction of any substantive content because (a) he doesn’t allow us to say anything meaningful about the “essence” side of the distinction and because (b) he lumps everything meaningful that we can say under the category of “energies,” which effectively trivializes that category by drawing the distinction in the wrong place. God’s “energies” should be properly conceived of as things God does or can do, not as anything that might be thought or said about God.

Third, extreme apophaticism sunders any meaningful connection between God’s essence and energies. As Palamas says, “‘the essence is known from the energy,’ but only with respect to ‘the fact that it is, not what it is'” (Pino, p. 54). In other words, our experience of God’s energies points to the existence of a source (God) but tells us nothing about that source other than that it is there. If this is right, then our experience of God’s goodness and love leaves us completely in the dark about whether God essentially is good and loving as opposed to superficially appearing good and loving (so far). The latter is consistent with God not being good and loving at all. This is catastrophic and unbiblical. The Bible is very clear that we can know God (John 17:3) and know that God is good (Romans 2:4) and loving (1 John 4:8). How can we fully trust God if we can’t know that God is essentially—not just accidentally, occasionally, or superficially—trustworthy?

3.2.4. A better way forward for Eastern Christianity

Fortunately, not all Eastern Christians are on board with extreme apophaticism. Despite its Palamite pedigree, that idea should be thoroughly repudiated. I understand Eastern Christian reluctance to break openly with one of their foremost saints, but there are times when it should and must be done. Individual saints, however venerable, are not infallible. It is only the corporate Church as a whole that can claim Christ’s promise that “the gates of hell shall not prevail” (Matthew 16:18).

In place of extreme apophaticism, it should be clearly affirmed that we can and do know things about the divine essence. If that sounds hubristic, just add qualifiers: we can only understand the divine essence partially and incompletely. We, as finite creatures, cannot fully comprehend the God who can do “more than we can ask or imagine” (Ephesians 3:20), but we can and do have substantive knowledge of God nonetheless.

Eastern Orthodox scholar David Bradshaw has helpfully pushed for recognition of the fact that God has contingent energies in addition to natural energies, specifically in order to make sense of divine freedom (§2.1) and God’s responsiveness to creation (§2.2) (Bradshaw, p. 25). Palamas scholar Tikhon Pino says that Bradshaw’s talk of God’s contingent energies is “controversial” (Pino, p. 22). Whether this is so or not, it shouldn’t be. More scholars need to pick up the contingent energies / natural energies distinction.

Another Eastern Orthodox theologian noted by Pino is Nikolaos Loudovikos. According to Pino, Loudivikos stresses the continuity between God’s essence and natural energies. Although “God is always more than his essential expressions,” says Loudivikos, the divine energies are “the essence ‘expressed'” (Pino, p. 23; see also p. 42, n. 160). This is a helpful emphasis because it means that, while the divine essence and natural energies are formally distinct, our participation in God’s natural energies yields genuine (albeit limited) knowledge of God’s essence.

Dr. Rhoda:

I confess that I’m still not entirely clear that the extreme apophatic view could possibly ever be refuted given this distinction (which of course we could reject, so we’re not bound to anything disastrous). I do not see how we can have even partial understanding of the divine essence such that “we can and do have substantive knowledge of God nonetheless.” I can’t see any argument for that, unless “It’s unbiblical” is meant to be the argument, which would be unpersuasive to the extreme apophaticist who might argue that the scriptures speak of human encounters with the divine energies alone and cannot be taken to provide us substantive knowledge of the divine essence. (Moreover, it’s not clear to me that the extreme apophaticist can even know THAT the divine essence is there, or that God even has any non-contingent energies, which is sort of a concern that the apophaticist isn’t apophatic enough.)

I’m also uncertain where the person of God is supposed to be in this model. If the essence is what God is and the energies are what God does, then it would appear that the argument is that God is essentially personal who “does personing” through his energies, so to speak. But are we really interacting with God as such, or with God’s energies? How could we be interacting with the divine essence at all, even “through” the energies? Are the energies mediating God’s essence interacting with us , or are they some sort of phantasm or theophanic projection of person-like energies that mimic but are not actually the essential personhood of God? I’m unclear whether we can personally interact with God at all on this model, and I’m also not sure whether God can actually be personal in any coherent and recognizable sense. (And if the person of God is entirely within the energies, then God isn’t essentially personal, which could perhaps still be made to work but sounds problematic, to say the least.)

Also the incarnational model you’re proposing in section 2.3 seems like it cannot be conciliar or orthodox since it doesn’t give you a Christ that is fully human. But you express concern for the apophatic view not being conciliar and appear to count this as a point against it. Are councils and orthodoxy important or not? I know you describe what you’re talking about in more detail in Side Note #3 of the above post, and assert below that you think it’s orthodox, but I think your explanation there only makes Christ look not human at all. (It sounds sort of Apollinarian, in spirit if not in fact.)

Hi Fred,

Thanks for the engaging comment. I can’t address everything you say, but I’ll try to respond to your three main points.

(1a) You first question “how we can have even partial understanding of the divine essence.” As to the “how” I say that we understand the divine essence to the limited extent we do through the divine energies. That is, we understand what God is (essence) by observing and experiencing what God does (energies) in creation, in our conscience, in the Scriptures, and most emphatically in Christ.

(1b) Perhaps you grant all that personally but wonder how this could refute the extreme apophaticist. In the first place, the above isn’t intended to “refute” the apophaticist. It doesn’t need to be because apophaticism is self-refuting. It basically says, “We know that we cannot know anything about God’s essence.” But that itself is a claim to know something about God’s essence, namely, that nothing can be known about it. Moreover, to affirm an essence–energies distinction is to affirm something about the divine essence, namely, that it is distinct from the divine energies. One who knows absolutely nothing about the divine essence is in no position to make such a claim.

(2a) You next ask “where the person of God is supposed to be in this model.” Speaking strictly as a Trinitarian, there is no such thing as “the” person of God for there are three Persons. God is essentially tri-personal, not mono-personal. As Gregory of Nyssa argued, because the divine Persons share a common instance of the divine nature, they share a common divine mind and will. So they always act in concert, but not always in the same manner (e.g., the Son hypostatically unites Himself to humanity but the Father and Spirit do not). The various divine energies are the various activities of the divine Persons.

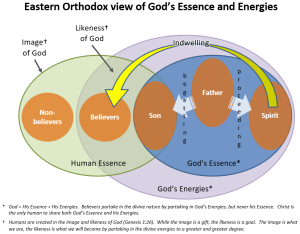

(2b) You then ask “But are we really interacting with God as such, or with God’s energies?” Both. God’s energies are distinct from the divine essence, but they are not separate from God. (See the diagram at the top of the post.) God is “in” the energies similar to how the Sun is “in” its rays. The Bible says that in Him, i.e., in God’s energies, “we live and move and have our being.” We are never cut off from God because the divine energies by which we live tie us to God. God may be differently active in believers and non-believers, but all of us participate in God’s sustaining energies.

(3) Finally, you say that my Christological model “sound sort of Apollinarian.” I deny the charge. Basically, though, in setting up a “‘human-sized’ psychological space” with His own Person, the Son enhypostasizes a complete human nature. The incarnate Christ has a complete human mind, will, and body, and Christ’s human mind and will are functionally distinct from the Son’s divine mind and will. The only way my model could collapse into Apollinarianism would be if the “‘human-sized’ psychological space” was not really distinct from the Son’s divine mind and will. But that’s explicitly excluded by the fuller model as I articulate it in the linked post. Of course, one also has to be careful not to overdue the distinctness and thereby slip into the opposite error of Nestorianism. I submit that my full model is compatible with conciliar orthodoxy. Why do you think it makes Christ “look not human at all”?

It’s a bummer for me that I discovered this blog during a busy work week. I’m definitely going to be diving into some of your articles when I finally get time!

I am a Melkite Catholic. My wife and I actually changed ascription from Roman Catholicism, due to a spiritual tugging Eastward.

I’m not a theologian. So I have to understand these concepts via very simple analogies. I will confess that I have only glossed over this article, but I really do want to dive into it this weekend. So, forgive me if this simple analogy is totally unrelated.

The sun is God in his essence. The light from the sun is God’s energies. The increase in heat in anything that the Sun’s light touches can be thought of as created Grace. Or, if we want to think of the human person in this analogy as being a plant, the Sun’s light triggers photosynthesis, and the process of photosynthesis could be seen as created Grace.

For me and my daily life that seems to be a neat enough reconciliation of concepts from the east and west. I also think in terms of theosis, that the beatific vision does not necessarily mean that we will be diving into the sun and that’s it. We are finite creatures infinitely drawn into the infinity of the sun via the Sun’s light. The beatific vision is therefore still a process or movement in my mind, rather than a finality.

Anyway, like I said I have only glossed over your article and I’m going to give it the attention it deserves later on this week.

Hi Colin. Thanks for the comment! I had to look up Melkite Catholicism. It’s Eastern-rite from what I gather. I like your adaptation of the Sun analogy. It shows, I think, that the notion of “created grace” is compatible with Eastern Orthodoxy *provided that* not all grace we receive is created. In terms of the analogy, the effect of the Sun’s rays (created grace) is no replacement for the Sun’s rays themselves (God’s uncreated energies). For Orthodoxy, the fundamental, transforming graces we receive are, and must be, uncreated. There could be no theosis were it otherwise.

As to whether the analogy helps to reconcile East and West, I don’t think it does. So long as the West affirms absolute divine simplicity, it has no metaphysical room for uncreated grace or an essence–energies distinction. For any substantive reconciliation to be possible, absolute divine simplicity has to go. But Rome is deeply committed to that idea, and it’s hard to see how it could change on something so basic without undermining the distinctive authority claims of the papacy and magisterium.

Dr Rhoda, I would think the sun’s rays can be seen as analogous to sanctifying grace, which in my non-theologion understanding is uncreated as it’s essentially the indwelling of the Trinity into a person. Here’s where my analogy probably fails because plants don’t prgressively become light.

I agree with you to an extent about Rome, for what it’s worth. And actually the Melkites have a contentious history with the Vatican 1 Church, as my wife and I found out in what constitutes our Eastern formation. I look at Rome with patient amusement. It seems like in recent decades whats been baked into papal supremacy is also that it’s th Magisterium’s prerogative to change it’s mind. It’s looking like supremacy has been taking Rome back to basics, in a sense, with this notion of synodality.

Pingback: Critiquing Craig on Divine Conceptualism and Aseity – Open Future