This is a reply to a recent critique of open theism by philosopher David Hunt on a YouTube channel called The Analytic Christian. The video interview was mainly focused on an essay Hunt wrote titled “What Does God Know? The Problems of Open Theism”. It was published in 2009 as part of an edited collection, Contending with Christianity’s Critics, which I reference hereafter as CCC. (Incidentally, Hunt is very clear in the essay that despite the title of the book, he does not endorse the claim that open theists are not Christians (CCC p. 266).)

I’m responding to Hunt in part because near the end of the video he replies to an argument I offered for open theism on the same channel 7 months previously. I was hoping he would give me a serious challenge, but unfortunately he doesn’t fully engage with my argument because (1) he didn’t watch the video wherein I presented the argument, and (2) the slide from my video that he comments on does not fully convey the nature of the new information given by the resolution of future contingencies. As a result, Hunt’s reply misses the central point of my argument.

In addition, there are several inaccuracies in Hunt’s critique, both in the video interview and in CCC, that are worth pointing out because appreciating such nuances is necessary for raising the level of discussion concerning open theism. Hunt’s work is by no means shoddy—he’s an accomplished and skilled philosopher—but he hasn’t thought through some of the issues as carefully as might be desired. My comments mainly focus on the video, to which I provide timestamps throughout, but here and there I will reference the published paper as well.

I. (1:52) – Question: What is open theism?

Hunt’s answers (with my comments):

-

- It’s an offshoot of Arminianism (1:57). (Yes and no. This is true of most modern Christian open theists, but it is not true of open theism per se. There were open theists before the Reformation, and thus before Arminius. In addition, there are Roman Catholic and Eastern Orthodox open theists. And there are non-Christian, e.g., Jewish, open theists.)

- At least some of the future is not predetermined but contingent (2:07). (Correct. All open theists would accept this.)

- At least some of those future contingencies concern human actions (2:16). (Generally correct, but not a strict entailment of open theism. In theory one could be an open theist purely for reasons having to do with physical indeterminism, independently of human actions.)

- Open theists operate with a libertarian conception of human freedom that is incompatible with determinism (2:29). (Generally correct, but not a strict entailment. See comment on I.3.)

- Open theists hold that at least some human actions exhibit libertarian free will (2:40). (Generally correct, but not a strict entailment. See comment on I.3)

- Open theists deny that God knows the contingent future (3:05). (Incorrect. Most open theists believe God does know the contingent future, but He knows it as contingent. That is, God knows the future as open-ended insofar as and precisely because it is open-ended. This is in contrast to the mainstream view that God somehow knows the contingent future as though it were fully settled even though, causally speaking, it isn’t.)

- The God of open theism knows “less” than the God of classical theism (3:10). (Emphatic no! This is a straw man. Most open theists believe God’s knowledge of reality is exhaustive. We disagree with what Hunt calls “classical theism” over the content of God’s omniscience, not its extent. Compare the dialectical situation with that between a Molinist and an anti-Molinist (say, one who thinks the grounding objection is decisive). Would it be right for the Molinist to boast that his God knows more than the anti-Molinist’s because his God has middle knowledge? No! That would be question-begging. The anti-Molinist doesn’t think middle knowledge could even possibly exist, so to him it’s like boasting that God “knows” something that isn’t even there to be an object of knowledge. From the anti-Molinist’s perspective, such pseudo-knowledge is a defect that detracts from God’s omniscience, for it means that God falsely “knows” things that just ain’t so, like your crazy neighbor who “knows” that aliens are watching him. For another comparison, this is like saying “My God is more powerful than your God because my God can make 1+1=17 and also make an 11-sided triangle.” Yeah, right.)

- Open theists sometimes call their view “dynamic omniscience” (3:19). (Correct. Open theist John Sanders coined the term “dynamic omniscience” as an alternative label for open theism, one that puts more emphasis on the changing content of God’s omniscience. It should by noted, though, that dynamic omniscience is not synonymous with open theism. Process theists and ancient figures like Cicero and Alexander of Aphrodisias affirm dynamic omniscience but aren’t open theists because they aren’t theists in the relevant sense.)

- On dynamic omniscience the content of God’s knowledge “grows” over time (3:28). (Incorrect. The content changes over time as future contingencies become resolved, but it does not grow or increase over time. The change is from a “maybe” to an “is”, from one truth to another truth. It is not the addition of “more” truths than there were before. See comment on I.7.)

II. (4:01) — Question: What’s the classical view of God’s omniscience?

Wrong question. Most open theists don’t have a different understanding of omniscience; rather, they have a different understanding of the content of God’s omniscience, i.e., of what a God who knows all truths and all of reality thereby knows.

Hunt’s answers (with my comments):

-

- Classical theists can differ on a lot (4:05). (True, but Hunt is using the term “classical theist” in a very broad sense to mean, roughly, any theist who isn’t an open theist. He should make this clear stipulation because the term “classical theism” is standardly used for a much stricter conception of God, one according to which God is absolutely simple, timeless, wholly impassible, purely actual, etc. Even Hunt’s own “Arminianism” would not count as a form of “classical theism” on that conception.)

- “Classical” theists differ on whether God knows from “within” time or “outside” of time (4:15). (True, but this is an uncritical use of inside/outside language and it begs important metaphysical questions. In effect, it spatializes time, conceptualizing it as a container of sorts, one that God could be either “in” or “out” of. By and large, theists who affirm a temporal conception of God should resist the inside/outside framing of the issue.)

- “Classical” theists agree that God knows the “entire” future including any future contingents (4:51). (So do most open theists. There’s a subtle issue here about what it is for something to be a future contingent. Suppose it is a future contingent whether Hunt eats a BLT tomorrow. If God knows that Hunt might eat a BLT tomorrow, does God know a future contingent? I would say so. God knows that future contingent as contingent. In similar fashion, I would say that God knows all future contingents. Now obviously that’s not what Hunt means by “future contingents”. Like many philosophers of religion he just assumes that future contingents must be understood exclusively in terms of what either will or will not happen. But this way of framing the concept tends to prejudice the debate against open theism.)

- “Classical” theists agree that God’s knowledge is exhaustive of past, present, and future (5:03). (So do most open theists. The debate concerns the nature of the future. For Hunt’s “classical” theist, “the future” refers to a complete linear extension of the actual past and present. For most open theists, “the future” refers to a branching array of possibilities.)

Notice that in answering this question Hunt has not said anything in points 1–4 that clearly demarcates his “classical” theism from open theism.

III. (5:19) – Question: Would a non-open theist say that God “gains knowledge” over time simply because what time it is now changes?

This question presupposes a dynamic (i.e., A-theory) of time. On such a conception God’s knowledge would have to continually change so as to track reality. Moreover, it would have to change in the same sort of way that most open theists believe God’s knowledge changes to track reality. For open theists, however, it’s not just the now that changes but also the modal configuration of the future, as branching possibilities are resolved into settled actualities.

-

- “If you’re a classical theist you’ll hold to God is in time” (5:59). (Um, no. Many if not most self-professed classical theists would take strong exception to that!)

IV. (7:06) – Question: What are three ways that open theists have tried to respond to the charge that God knows “less”?

The question comes more or less straight out of CCC (p. 268), but it’s poorly framed for reasons I gave in I.7 above.

-

- Open theist Greg Boyd responds that God knows more on open theism because God knows all possible futures, but the “classical” God knows all possible futures too (7:15). (Hunt’s response is correct. There’s no meaningful sense in which God knows more or less on either view. Open and “classical” theists differ over the content of God’s knowledge, not the extent of God’s knowledge.)

- Most open theists agree that God on their view knows “less” and argue that this doesn’t count against God’s perfection (7:50). (Emphatic no with respect to God knowing “less”! See my comments on I.7 above. Hunt is correct, though, that open theists reject the idea that their views compromise God’s perfection.)

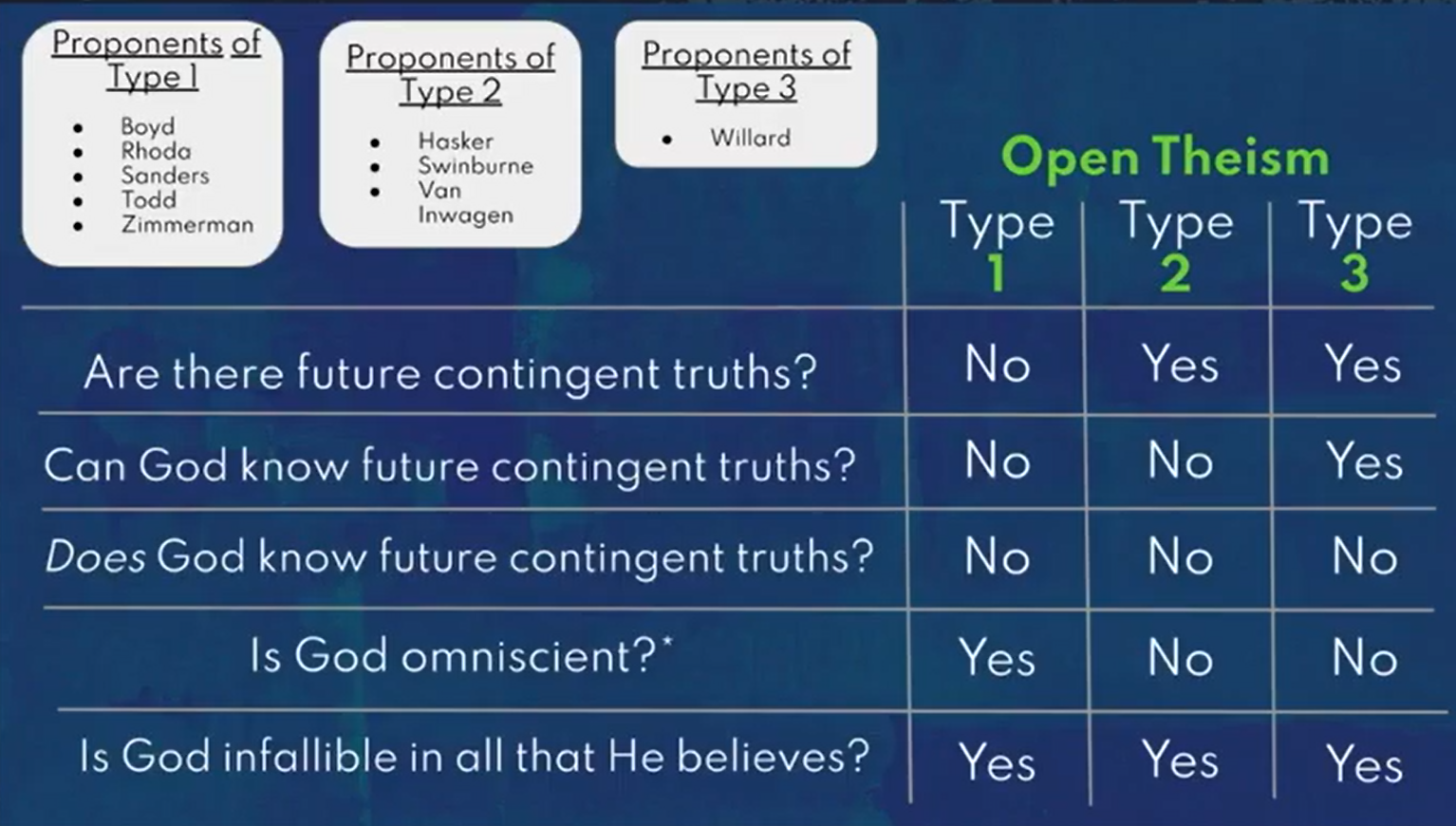

This brings us to Hunt’s first slide, which describes three types of open theism:

Hunt spends the next 10 minutes or so explaining the slide. Before discussing some of what he says in that context, I want to make some preliminary remarks about the slide itself.

-

- First, this breakdown between three types of open theists is reasonably accurate. I would explain the types as follows:

- Type 1 open theists affirm that God is unqualifiedly omniscient by insisting that there is no such thing as a unique and complete actual future for God, or anyone, to know.

- Type 2 open theists believe that there is a unique and complete actual future, but deny that it is knowable insofar as the future is contingent.

- Type 3 open theists believe that there is a unique and complete actual future and they believe that it is knowable, but they do not believe that it is actually known because God voluntarily suppresses His knowledge of how the contingent future is going to play out.

- To my knowledge, the proponents listed for each view are accurate with the exception of Hasker, who since 2021 at least has switched from Type 2 to Type 1 open theism.

- The term “future contingent truths” needs to be defined. See my comments on II.3 above. If “Hunt might have a BLT for lunch tomorrow” counts as a future contingent truth, then all 3 types of open theist should answer “Yes” to each of the first 3 questions. Hunt presumably means to limit “future contingent truths” to propositions asserting truly that a future contingent will or will not happen. On that understanding the breakdown for the first 3 questions is correct.

- The asterisk on question 4 isn’t explained. I presume it’s intended to flag the term “omniscient”. All open theists believe that God is aptly described as “omniscient”, but they don’t necessarily mean the same thing by the term. Type 1 open theists have an unqualified view of God’s omniscience—God literally knows all truths and all of reality. Type 2 and Type 3 open theists affirm a qualified view of God’s omniscience, with Type 2 saying that God knows all that is knowable and Type 3 saying that God knows all knowable things that He wants to know. If “omniscient” is understood in the unqualified sense, then the Yes/No/No breakdown for this question is correct.

- The last question “Is God infallible in all that He believes?” is problematic. If this is understood to mean that God is infallible in all that He believes with certainty, then the Yes/Yes/Yes breakdown is correct. There is no way that God can be certain that X occurs and X not occur. But if “believes” allows for less-than-certain degrees of credence, then all 3 types of open theists would answer No/No/No. Compare Isaiah 5:4 where God “expects” His vineyard to bring forth good grapes, but it doesn’t. That seems like a case where God had less than maximal credence.

- First, this breakdown between three types of open theists is reasonably accurate. I would explain the types as follows:

V. (8:30) – Hunt’s comments on the above slide

-

- The open theist God knows “less” than the “classical” theist God (10:35). (Incorrect. See my comments on I.7 above.)

- That there are future contingent truths seems to be as clear a “datum” as possible (12:17). (Hmm. If determinism is true, then there are no future contingent truths of any sort. So is the falsity of determinism a datum? I’m as much inclined to think determinism is false as Hunt is, but I wouldn’t say it’s a “datum” and certainly not one that is “as clear as possible”. I doubt our theistic determinist friends would be much impressed by us free-will theists simply pounding the table that determinism is wrong!)

VI. (20:07) – Question: What are some reasons to reject open theism?

Hunt’s answers (with my comments):

-

- We need to approach this question in a charitable spirit because we “see as in a glass darkly”. All of these reasons have reasons on the other side. (21:37) (Agreed. I commend Hunt for his expression of intellectual humility and his charitable attitude. The issues are many, subtle, and intertwine in complex ways, so even as we forcefully state our respective positions, it’s naïve to expect easy knockdowns.)

- There are Scriptural passages than can be used as prooftexts for a traditional conception of God’s foreknowledge, e.g., Psalm 139:4 “before a word in on my mouth you know it” (21:50). (Yes, there are plausible prooftexts for the traditional conception, but Psalm 139:4 is not a good one. The passage explicitly grounds this knowledge in God’s intimate present acquaintance with David. It’s like when one person says to a close associate, “I know what you’re about to say”. This verse implies nothing about God’s having known everything David would say from eternity past. Psalm 139:16, which Hunt references later at 53:39, may seem like more challenging text for the open theist, but in context “the days fashioned for me” seems to refer to the days of David’s intra-uterine gestation, not his entire life. Calvin himself took the verse that way.)

- Some open theists think Scripture is their strong suit because there are lots of openness-friendly passages (22:24). (Correct. Even if not decisive, the Biblical case for open theism is a lot stronger than most Christians realize.)

- So we have Scriptural “evidence in tension” and the question is how well each side can deal hermeneutically with the other side’s texts (22:48). (Agreed.)

- I don’t think the debate can be settled with Scripture (23:16). (I’m inclined to agree in that how we interpret Scripture is highly influenced by our background assumptions. I doubt we can resolve the debate over open theism without looking closely at those assumptions and thus without venturing in philosophy.)

- Tradition points more unequivocally in favor of “classical” theism. (23:25) (I concede this point. The key questions are why this is so and how strongly it counts against open theism. I’ve argued elsewhere that tradition does not constitute a strong argument against open theism for roughly the same reason that it doesn’t count strongly against heliocentrism—it just wasn’t a big issue during the first few centuries because everybody just assumed geocentrism, and by the time it became a big issue with Copernicus and Galileo it was mainly philosophical rather than strictly Biblical considerations that were driving the geocentrism bus.)

- Open theism is an innovation (24:00). (This is not so clear. From the extant writings, the dominant view among the early Church Fathers seems to have been the simple foreknowledge view. But open theism in some form may have been a minority report from the beginning, albeit one that didn’t leave much of a paper trail, whether because it just wasn’t enough of issue or because such ideas were culturally and/or politically suppressed. From Cicero (106–43 BC) and other ancient sources we know that the practice of divination was ubiquitous in Greco–Roman culture and thus that the possibility of local divine foreknowledge (i.e., of specific events) was largely just assumed. But that’s consistent with a denial of global divine foreknowledge (i.e., of all events), so there remained at least some conceptual space for open theism. John Sanders informs me that he once had in his possession (but now seems to have lost!) documentation suggesting the existence of pre-Christian Rabbinic open theism. In any case, we known from Calcidius (ca. 320 AD) that open theism was present around the time of the First Council of Nicea (325 AD). After Augustine (354–430 AD) classical theism (in the strict sense of the term) became increasingly entrenched and eventually effectually, if not quite officially, dogmatized in the Western Church. The Eastern Church, with its deep apophatic leanings, has always remained much less willing to pin God down.)

- There’s no doubt that the tradition was influenced by pagan philosophy esp. Neoplatonism (24:41). (Correct.)

- As a “Neoplatonist”, I tend to think that the influence of philosophy on Christianity was “beneficent” (25:13). (What exactly does Hunt mean by the “Neoplatonist” label? It’s not surprising that some aspects of a broad and diverse system like Neoplatonism—for example, the identification of God with the Good—are congenial to Christianity, but other important features of Neoplatonism, such as its emanationist view of creation, its subordinationist model of the Godhead, and its denigration of material reality, are incompatible with Christian orthodoxy and closer to Gnosticism.)

- Decisive philosophical considerations trump appeals to tradition (e.g., if traditional foreknowledge is conceptually impossible, then so much the worse for tradition) (25:28). (Agreed.)

- Some open theists believe the problem of evil counts in favor of open theism because the less God knows about the contingent future the less we can hold Him responsible for it (25:55). (This is true, but mainly because (a) creaturely freedom is important for the free-will theodicy, (b) meticulous providence is hard to square with creaturely moral evil. Lacking simple foreknowledge is only relevant if simple foreknowledge is providentially useful. Pace Hunt, it isn’t. In CCC pp. 280–281 Hunt contends that simple foreknowledge is providentially useful, but he misframes the issue as a universal generalization to the effect that “all instances of foreknowledge are providentially useless”. And then he proceeds to supply a counterexample wherein God uses foreknowledge that X to prepare for events downstream of X. But this is the wrong way to frame the issue. The open theist argument for the disutility of simple foreknowledge is based on the observation if God’s knowledge that X explanatorily depends on the actual occurrence of X, then God’s knowledge is useless with respect to X. Hunt actually agrees with this (see p. 281)! Moreover, if God’s foreknowledge is exhaustive, as Hunt maintains, then this is true for all future contingent X. In each case the knowledge explanatorily depends on the actual occurrence, by which time it’s too late in the explanatory order to do anything about those events. Hunt’s counterexamples can only gain purchase in a limited foreknowledge situation where God’s knowledge of events downstream of X is what it would be given open theism from that point on!)

- Even on open theism, God needs to have good reasons for not intervening to prevent evils that He could have prevented. How is that any better than what non-open theists can offer? (27:54). (No one claims that open theism has an easy time with the problem of evil. The argument, rather, is that open theism is comparatively better off than models that either deny creaturely freedom or affirm meticulous providence. For open theists, moral evil is always tragic—it is merely permitted by God and never specifically willed by God. God only wills the possibility of moral evil (for a greater good), not its actuality. Molinists and theistic determinists can’t say that. For them every instance of moral evil is part of God’s sovereign plan by which He ordains “whatsoever comes to pass”. So God wills the actuality of moral evil (for a greater good) on those views, and nothing is merely permitted by God. Consequently, God is much more complicit in moral evil given meticulous providence than He is on open theism.)

VII. (29:15) – Question: How might you respond to an open theist prooftext?

Hunt’s answers (with my comments):

-

- Hunt references Isaiah 5:1–4, in which God “expects” a vine to produce good grapes but it only produces will grapes. (29:39) (This is a popular open theist prooftext. As Hunt notes, if God expects something and it doesn’t happen, then it suggests that He didn’t have infallible foreknowledge of that thing’s happening.)

- One way a “classical” theist can handle this passage is to suppose that “expect” is being used in a prescriptive sense (e.g., “I expect you not to plagiarize”) rather than in an epistemic sense (30:29). (This doesn’t seem plausible to me because in the opening metaphor (vs. 1–2), the vineyard is a nonsentient object, not a moral agent, and so prescribing grapes of it doesn’t make any sense. It’s only when we get to the moral application of the metaphor (vs. 3–4) that the prescriptive reading of expectation has any plausibility. The epistemic reading, however, makes good sense throughout. So either we’re inexplicably shifting senses in the middle of the passage, or it’s epistemic throughout.)

- Open theists are going to have trouble with other passages, such as Peter’s denial (31:35). (Agreed. Open theists who take the Bible seriously have to find exegetically plausible responses to “classical” theist prooftexts. The Peter example is not particularly difficult, though. In CCC pp. 272–273 Hunt briefly discusses the Peter example but is very dismissive of three open theist suggestions that he mentions but doesn’t develop. It’s pretty easy to dismiss suggestions when you haven’t really given them a chance.)

- We all have trouble with some passages and engage in what the other side regards as “strained exegesis” (31:45). (Agreed.)

VIII (32:30) – Question: What other philosophical arguments do you want to consider?

Hunt proposes focusing on the Type 1 open theist claim that there aren’t any future contingent truths. See my comments on the slide above (section IV bullet points) about the need to specify more exactly what’s meant by “future contingent truths”.

For about 15 minutes, Hunt talks through a new and overly complex slide, the point of which is to argue (1) that a proposition like “Dave Hunt eats a BLT at time T” is true at all times solely in virtue of what happens at time T and (2) that it is true at all times solely in virtue of what happens at time T because the proposition is allegedly wholly about (what happens at) time T. So if Hunt eats a BLT today, then it was allegedly true yesterday that Hunt was going to eat a BLT today and, similarly, it will be true tomorrow that Hunt ate a BLT today.

I have several points to make in reply:

-

- First, even granting that “Hunt eats a BLT at time T” is wholly about (what happens at) time T, it is nevertheless false that the future tense proposition “Hunt will eat a BLT at time T” is wholly about time T. Similarly it is false that the past tense proposition “Hunt ate a BLT at time T” is wholly about time T. Indeed, it is precisely because these propositions are tensed that they cannot be wholly about time T. This is because all tense is rooted in the (speaker’s) present and can then point forward or backward from there. Without an anchoring in the present, you don’t have a future or past tense, or even a present tense for that matter. It’s easy to overlook this feature of language because the future and past tenses point our attention away from the present. Nevertheless, they are still anchored in the present.

- Thus, to say that X will happen is not primarily to say something about the future, but rather to say something about the post-present.

- Likewise, to say that X happened is not primarily to say something about the past, but rather to say something about the no-longer-present.

- So the past and future tense versions of “Hunt eats a BLT at time T” are not wholly about time T. They are also, and primarily, about the present.

- Second, it is because the past and future tense versions of “Hunt eats a BLT at time T” are not wholly about time T that the truth of those propositions cannot be wholly grounded in what happens at time T. The truth has to be grounded in present conditions such as it’s going to be such that Hunt eats a BLT at time T or it’s having been such that Hunt eats a BLT today.

- The first, it’s going to be such that Hunt eats a BLT at time T, is about how the present bears upon the future. How is the present such that that future will obtain?

- Now if the present is indeterministic with respect to whether Hunt eats a BLT tomorrow, then the present is not such that Hunt will eat a BLT tomorrow because whether he will eat a BLT is objectively an open question—reality could still go either way on this. This is why Type 1 open theists insist that will and will not propositions about future contingents are not true in advance.

- The second, it’s having been such that Hunt eats a BLT today, is about how the present preserves the past. How is the present such that that past obtained?

- At (44:39) Hunt objects, “imagine that God stamps out all causal traces of my eating a BLT today?” Reply: God can’t do that. One of those causal traces is God’s own memory of that event, and God can’t erase that. Even if all other causal traces vanish, God’s memory necessarily perfectly preserves the past in the present.

- The first, it’s going to be such that Hunt eats a BLT at time T, is about how the present bears upon the future. How is the present such that that future will obtain?

- Third, the need for present grounding can also be made by pointing out that on Hunt’s account it is true now (let’s say) that Hunt will eat a BLT tomorrow. Well if it’s true now, then what makes it true now? It can’t be tomorrow’s BLT eating because:

- That event doesn’t exist yet (unless we presuppose an eternalist model of time)—nonexistent grounds are no grounds at all. (The parallel argument about the past no longer existing doesn’t work because God’s memories guarantee the persistence of truthmakers for truths about the past.)

- Even if we assume eternalism, all that follows is that it’s true simpliciter that “Hunt (tenselessly) eats a BLT at time T”. It doesn’t follow that it was true at all times before T that Hunt will eat a BLT at time T. This is a non sequitur. To avoid it we would need an additional mechanism, like time travel, backward causation, or crystal ball “magic”, to carry information from future times to past times.

- In any case, future contingency is incompatible with an eternalist ontology for the same reasons I give in my YouTube argument for open theism and for reasons I give in this paper.

- First, even granting that “Hunt eats a BLT at time T” is wholly about (what happens at) time T, it is nevertheless false that the future tense proposition “Hunt will eat a BLT at time T” is wholly about time T. Similarly it is false that the past tense proposition “Hunt ate a BLT at time T” is wholly about time T. Indeed, it is precisely because these propositions are tensed that they cannot be wholly about time T. This is because all tense is rooted in the (speaker’s) present and can then point forward or backward from there. Without an anchoring in the present, you don’t have a future or past tense, or even a present tense for that matter. It’s easy to overlook this feature of language because the future and past tenses point our attention away from the present. Nevertheless, they are still anchored in the present.

- An objection by Hunt:

-

- (47:01) If Type 1 open theists are right about future contingent truths, then “we have a whole tense in natural language that has no purpose, the future tense”. Why? Because Type 1 open theists only believe we can use the future tense for non-contingent future events and there may be no such events (except for logical necessities like “it will be the case that 2+2=4 tomorrow”) because God can undo virtually anything.

- Hunt’s example: We might have thought that “Lincoln will still be dead tomorrow” is a non-contingent truth about the future, but what if God raises Lincoln like he raised Lazarus?

- (47:01) If Type 1 open theists are right about future contingent truths, then “we have a whole tense in natural language that has no purpose, the future tense”. Why? Because Type 1 open theists only believe we can use the future tense for non-contingent future events and there may be no such events (except for logical necessities like “it will be the case that 2+2=4 tomorrow”) because God can undo virtually anything.

My reply: This objection is misguided for a couple reasons:

-

- There is much more to the future tense than just will and will not. That is what one might call the determinate future tense because it represents the future as determinate in some respect: this will happen. But there is also the indeterminate future tense, which points forward in time but represents the future as still somewhat open-ended. For example, “Hunt will probably have a BLT tomorrow” or “Hunt may have a BLT tomorrow”.

- Very often when people say that something “will” happen they are only saying that it’s highly expected or that’s it’s a present intention. For example, in a comment I posted on the video interview with Hunt I said “I will write up a blog response to this”. In saying that I wasn’t saying that it was then definitively true that I will write up a blog response—for all I knew, unforeseen circumstances may have prevented my doing so. What I was saying it that it was then my settled intention to respond to Hunt’s critique of open theism.

- There is no reason to think that there aren’t many non-logical necessary truths about the future. God has already considered all future possibilities and has decided which ones to leave open and which not to. Even if it is not certain that Lincoln will remain dead (because God intends there to be a future resurrection), it is certain that Lincoln will have been dead (future perfect tense). Indeed, at all future times, whatever has happened will continue to have happened.

- There is much more to the future tense than just will and will not. That is what one might call the determinate future tense because it represents the future as determinate in some respect: this will happen. But there is also the indeterminate future tense, which points forward in time but represents the future as still somewhat open-ended. For example, “Hunt will probably have a BLT tomorrow” or “Hunt may have a BLT tomorrow”.

IX. (49:56) – Question: How would you respond to Type 2 and Type 3 open theism?

Hunt’s answers (with my comments):

-

- Type 2 open theism has the burden of explaining why God can’t know certain truths (50:16). (Agreed.)

- “God knows the future by directly apprehending it” (51:10). (If Hunt isn’t endorsing eternalism here, then I don’t know know how the future can be there for God to apprehend.)

- Type 3 open theism, like all versions of open theism, is based on the argument that foreknowledge is incompatible with libertarian creaturely freedom, but that’s a bad argument (51:35). (Well, he hasn’t considered my argument yet! In any case, fatalistic arguments, when properly formulated, are not so easy to knock down. There are only two basic anti-fatalist strategies: open futurism and preventable futurism. Each faces challenges.)

X. (52:28) – Question: How would you respond to Alan Rhoda’s argument for open theism?

Hunt examines two slides from my interview. He did not watch the interview. All he knows of my argument is what he saw in those two slides.

-

- The first slide articulates four core commitments of open theism. Hunt doesn’t take much issue with this, though at 55:19 he wonders why I focus on epistemic rather than alethic incompatibility with future contingency. The reason is precisely to accommodate Type 2 and Type 3 open theism! Those types, unlike Type 1, do not accept alethic incompatibility arguments, but they do accept epistemic incompatibility arguments.

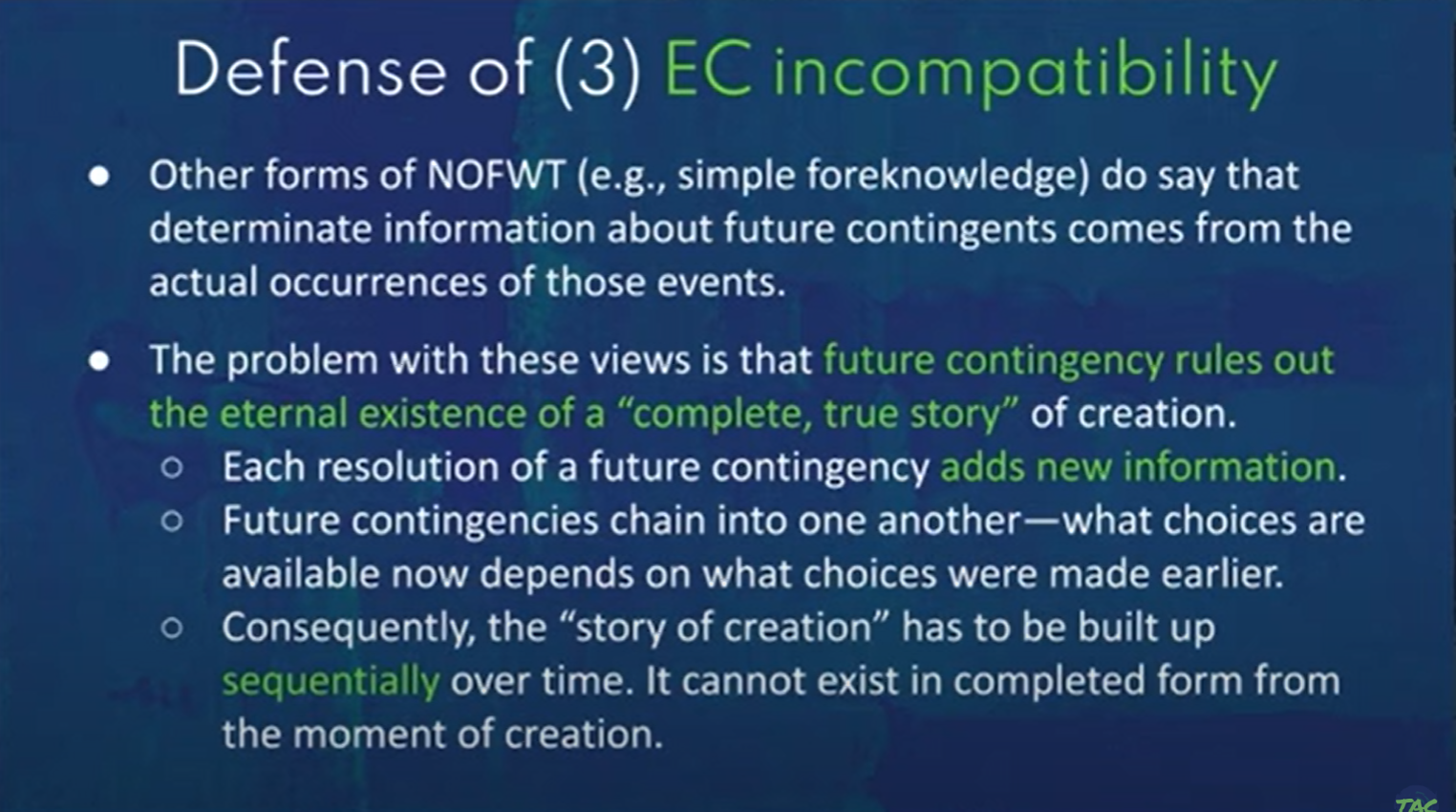

- The second slide presents my argument that, given future contingency, there cannot be an eternally complete “true story” of creation. Here’s the slide:

-

- Hunt’s response (starting at 57:17) is basically to agree (1) that determinate information about future contingents comes from the actual occurrences of those events, (2) that each resolution of a future contingency adds new information, and (3) that future contingencies chain into one another and then to disagree that it follows from (1–3) that (4) the “complete, true story” has to be built up sequentially over time as contingencies are resolved.

- He disagrees that (4) follows from (1–3) because it seems to him that his own model (described in section VIII above) can accommodate each of (1–3).

- At 59:22: “It’s the events, what happens, that produces new information as the events unfold, that chain into one another, and build up sequentially over time, but I’m not sure how one gets from that to there not being any complete, infallibly known story about those events which [story] exists in complete form from the moment of creation.”

In response:

-

- First, I grant that my argument for EC incompatibility isn’t presented in a fully rigorous way. I was trying to keep it accessible for a broad audience. I think that if Hunt had watched my presentation that he would have understood what I’m driving at.

- Second, the main reason Hunt doesn’t follow my argument is because he misconstrues the nature of the “new information” that I’m talking about.

- From his comments about “new information” both at 59:22 and at 1:00:09 it’s clear that he thinks this new information has to do with the occurrences of future contingent events. So, as he sees it, the information that Hunt eats a BLT at time T is eternally given by the actual occurrence of that event at time T.

- But that’s not what I’m talking about. The kind of new information I’m concerned with has to do with the resolution of future contingencies. That’s how I put it on the slide, and the word choice was deliberate.

- As I make clear in my presentation, by the “resolution” of a future contingency I mean a transition from an information state where it is an open question whether, say, Hunt eats a BLT at time T, to a new information state where that question is settled by the actual occurrence of that event. Why does there need to be a transition? Because, if there are future contingents, then before such events (in the explanatory order) it is really possible for reality to go in either direction (eat BLT or not eat BLT) and it is not yet (in the explanatory order) settled which way reality is going to go. The actual occurrence of a future contingency settles that question and thereby converts an open-question information state into a settled-question information state.

- My argument turns on the fact that these two information states (open-question vs. settled-question) are mutually incompatible. It can’t both be “up in the air” whether Hunt eats a BLT and a settled fact that he does. Hence the two information states can’t be realized concurrently, or at the same eternal moment. And that’s why the complete story has to be built up sequentially as contingencies are successively resolved and why it cannot, as Hunt puts it, exist “in complete form from the moment of creation”.